First of all, in order to initiate the step-by-step process, the team needs to get organised. This step involves clarifying the objective and scope, identifying technical and logistical requirements, and laying out a work plan. Its expected outputs are:

- A clear formulation of the broad aims and vision

- The core team is identified and access to relevant knowledge and expertise ensured

- A work plan, budget and funding plan.

Task 1 A. Specifying the vision, broad aims, and the spatial scope

What this task is about

The broad aims and visions should be clear from the beginning. A particular management issue, conservation or development challenge will drive the step-by-step process to identify policy and financing instruments. The aims behind selecting and planning an instrument will usually be refined during the process, for instance when deeper understanding of the situation and of local needs produces a more specific focus. For example, in biodiversity conservation the aims at the outset may be very broadly ‘to protect or enhance biodiversity’, but they could then become more specific: e.g. to counteract threats to certain ecosystems or species, to reduce certain pressures on a protected area, to improve crop diversity, etc. Similarly, livelihood objectives may focus specifically on resolving existing conflicts, or providing resource access for specific disadvantaged groups.

![]() Developing a policy or financing instruments is not an end in itself! Please click to learn moreAs obvious as it seems, it is important to keep reminding yourself that the development of a policy or financing instrument is never an end in itself, but a means to an end: in this case, strengthened biodiversity conservation and improved local livelihoods.

Developing a policy or financing instruments is not an end in itself! Please click to learn moreAs obvious as it seems, it is important to keep reminding yourself that the development of a policy or financing instrument is never an end in itself, but a means to an end: in this case, strengthened biodiversity conservation and improved local livelihoods.

In addition, the spatial scope or focal area should be made clear. Is it (part of) a protected area, a buffer zone, the territory of a particular community, a watershed, or an administrative area (e.g. district, department)? Bear in mind the need to be flexible: the focal area may change during the process. The instruments you eventually identify may only be relevant to part of the planned area, or cover a much wider one.

![]() Finding the right scale is important! Please click to learn moreIn Thailand, the ECO-BEST project started by looking at the whole DPKY World Heritage Site (WHS) as a potential pilot project area but it became clear that it needed to downscale. A stakeholder workshop was held to identify important issues in different areas of the WHS. Based on this workshop, Bu Phram sub-district was chosen as the project site. The main reasons for that were:1) the wildlife corridor in that particular area was important to UNESCO;2) the challenges (conflicts) seemed possible to solve within existing law and regulations;3) there seemed to be potential for scaling up a solution to other parts of the WHS, possibly even to other Thai protected areas. Last but not least, the site was relatively easy to reach from Bangkok, saving logistical effort and costs.

Finding the right scale is important! Please click to learn moreIn Thailand, the ECO-BEST project started by looking at the whole DPKY World Heritage Site (WHS) as a potential pilot project area but it became clear that it needed to downscale. A stakeholder workshop was held to identify important issues in different areas of the WHS. Based on this workshop, Bu Phram sub-district was chosen as the project site. The main reasons for that were:1) the wildlife corridor in that particular area was important to UNESCO;2) the challenges (conflicts) seemed possible to solve within existing law and regulations;3) there seemed to be potential for scaling up a solution to other parts of the WHS, possibly even to other Thai protected areas. Last but not least, the site was relatively easy to reach from Bangkok, saving logistical effort and costs.

![]() A good map of the area of interest can be an important tool! Please click to learn moreA map can support discussions and mutual understanding in the team about the scope and objectives, and can be very useful in communicating them to stakeholders. A map can also be useful for discussing the origin of ecosystem services as well as where their benefits accrue, or help to define explicitly where changes or activities need to take place.

A good map of the area of interest can be an important tool! Please click to learn moreA map can support discussions and mutual understanding in the team about the scope and objectives, and can be very useful in communicating them to stakeholders. A map can also be useful for discussing the origin of ecosystem services as well as where their benefits accrue, or help to define explicitly where changes or activities need to take place.

How to go about Task 1A

Your team should discuss and clearly formulate its aims and visions as well as the conservation and development issues to be addressed by a policy or financing instrument. Template 1 helps to specify the issues and aims. It distinguishes between short-term (1–5 years) and long-term perspectives (more than five years). Clear formulations will help you communicate to stakeholders what you are trying to achieve by using economic instruments, and to prepare inputs and suggestions for discussion at the first stakeholder workshop(s) (see Step 3). In order to make stakeholders feel comfortable with the whole process, it is important that they endorse the broad aims and visions and understand that the objectives will take account of their needs and perceptions. You should update the formulations in Template 1 A whenever more specific objectives are agreed.

![]() Template 1A: Broad aims / Mission statement (examples from Kochi, India) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Template 1A: Broad aims / Mission statement (examples from Kochi, India) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Task 1 B. Forming the core team and ensuring relevant expertise

What this task is about

Someone is of course the initiator of the process. This might be government staff in a department that aims to integrate conservation and development goals. It might be the project manager of a local NGO, an international conservation organisation, or even a developer from a company who wants to conduct business in a green way.

Although the exact team composition will vary depending on the aims and context of the process (as well as its budget!), key knowledge and skills will often include the following:

- Knowledge of the local conditions (incl. the organisational structure of communities)

- Ability to contact local people

- Knowledge of local ecology (e.g. forestry, wetlands, hydrology, etc.)

- Understanding of socio-economic conditions and legal issues

- Skills in participatory planning and management

- Knowledge and understanding of how to apply economic instruments successfully

- Skills in local enterprise development and small business planning

- Skills for stakeholder engagement and workshop facilitation

- Skills in designing and carrying out rapid field surveys.

It is not necessary for the core team to possess all these areas of expertise, but it will help if members have a firm grasp of many of them. For instance, if the process is initiated by a well-connected national park manager or NGO who already works in the area, then a key area of focus might be to engage expertise on more technical aspects of the ecological, political, and socio-economic knowledge base. If external research institutions or organisations are the initiators, a first step may be to ensure the participation and buy-in of stakeholders with local knowledge and networks, e.g. site-level conservation authorities or community leaders. Valuable support can come from people who may not be obvious at first: for example, school teachers, the local radio station, student organisations, clubs, or religious groups. These can prove vital, not only as a source of information but in giving positive energy and momentum to the project.

![]() Political contacts and networking matter! Please click to learn moreIn the ECO-BEST project in Thailand, in particular in Thadee, the project staff were native to the area and already knew local officials and political networks. This was extremely helpful in identifying where to get sup-port, from whom, and how to reach them. For instance, the local coordinator happened to have been a classmate of the vice-mayor of NST municipality and of the secretary to the Governor.Building personal relationships during the process played an important role and often had surprising effects. For instance, a joint dinner and karaoke event attended by the provincial governor’s assistant led to the governor attending a project workshop, which gave credibility to the process and impressed the stakeholders.

Political contacts and networking matter! Please click to learn moreIn the ECO-BEST project in Thailand, in particular in Thadee, the project staff were native to the area and already knew local officials and political networks. This was extremely helpful in identifying where to get sup-port, from whom, and how to reach them. For instance, the local coordinator happened to have been a classmate of the vice-mayor of NST municipality and of the secretary to the Governor.Building personal relationships during the process played an important role and often had surprising effects. For instance, a joint dinner and karaoke event attended by the provincial governor’s assistant led to the governor attending a project workshop, which gave credibility to the process and impressed the stakeholders.

It might be useful to distinguish between different divisions of responsibilities. For instance you could nominate a steering team and a technical support team, or distinguish between a strategic lead in charge of the overall process and an operating team coordinating day-by-day local operations.

Of course, experts for specific studies or analyses can be brought on board later in the process, especially when specific needs become clearer (e.g. moderators for the stakeholder workshop; ecologists for the detailed analysis of ecological functions). It can be helpful, however, to have experts in the loop from early on and ensure that they understand the purpose of the undertaking and are willing to contribute. An expert should be considered trustworthy and credible by everyone involved, including the relevant stakeholders. It is also a good idea to involve an expert in communication right from the beginning.

How to go about Task 1B

Discuss among you what expertise is needed for the process. The above bullet points showing the different types of expertise and knowledge will help you. Then, reflect on what expertise you already have and who could provide what’s missing. Template 1B can be filled out to document the necessary expertise and providers. Make sure you have a joint understanding of who is leading which aspects and how to take decisions as a team. How you work together and share responsibilities will also feed into the work plan to be made in Task 1C.

![]() Template 1B: Contributors to the process (Examples from Bu Phram, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Template 1B: Contributors to the process (Examples from Bu Phram, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Task 1 C. Making a work plan

What this task is about

Once the objectives and spatial scope have been specified and the core team formed, it is necessary to plan how the process will be carried out in practical terms. Preparing a work plan involves thinking through and organising four main aspects:

- The tasks to be carried out and outputs to be generated

- The inputs and budget required to carry out these tasks and deliver these outputs

- The schedule and responsibilities for delivering different components of the assignment

- How it will be funded and resourced.

For each task and output, this basic work plan will usually specify the start and end date, location, person(s) responsible for delivery and resources required.

Each identified task and output needs to be costed in terms of input requirements. Inputs are the intellectual, material, financial and other resources needed. Without sufficient resources, the process cannot be carried out. At a minimum, these should cover staffing and technical inputs, equipment, consumables and other materials, purchase of data, travel and transport expenses, meetings and workshop costs. Estimates should also be made of how long each task or output will take to complete. You need to consider both cash costs (i.e. those which involve purchases such as fuel or notebooks) and in-kind contributions (i.e. those which are free or already paid for, such as staff time, a meeting room, or use of a computer).

You need to ensure sufficient and timely funding and resourcing to cover the costs. Although an adequate budget is sometimes already available, in many cases it will be necessary to go out and search for funding, contributions, staff time and other inputs (or even to justify the use of already existing funds). Your budget and work plan provide the basic information for putting together a funding request or project proposal. Any contributions from partner communities, team members or their institutions (e.g. of time, materials or other resources) should also be confirmed at this point.

![]() How long the process takes, and what it costs depends on many factors! Please click to learn moreIt is difficult to give exact time and resource requirements for the process since they will depend on specific circumstances and what already exists in terms of project structures, contacts and net-works, and resources. Ideally the guidelines will support ongoing processes and build on available resources and an experienced team. In that case, the process could actually be very quick – let’s say 3 to 6 months. Short scoping studies that only use Steps 2–4 could be done in a few weeks. If starting from scratch, however, it could be 3–5 years before actual implementation of the instrument(s), as in the ECO-BEST sites in Thadee and Bu Phram. In difficult settings with conflicts or weak structures it could even take 10. In such cases, resource needs will tend to be considerably higher and sufficient funding will need to be secured along the way.

How long the process takes, and what it costs depends on many factors! Please click to learn moreIt is difficult to give exact time and resource requirements for the process since they will depend on specific circumstances and what already exists in terms of project structures, contacts and net-works, and resources. Ideally the guidelines will support ongoing processes and build on available resources and an experienced team. In that case, the process could actually be very quick – let’s say 3 to 6 months. Short scoping studies that only use Steps 2–4 could be done in a few weeks. If starting from scratch, however, it could be 3–5 years before actual implementation of the instrument(s), as in the ECO-BEST sites in Thadee and Bu Phram. In difficult settings with conflicts or weak structures it could even take 10. In such cases, resource needs will tend to be considerably higher and sufficient funding will need to be secured along the way.

How to go about Task 1C

Coming up with the input for the work plan obviously requires in-depth discussion and planning by the study team, but also offers a valuable opportunity for the whole team to discuss jointly and agree on why and to what ends the process is being carried out, what it needs to address, and which role each person will play in taking it forward. Carefully reading the overview of the steps and the guidelines in advance will help you understand what lies ahead. A training session using the guidelines could be an option at this point to ensure that the whole team fully understands the overall procedure. Then, a day’s meeting should be sufficient to brainstorm, discuss and agree on the assignment tasks, outputs, resource requirements, schedule and responsibilities. This involves asking ‘What do I need to do, use or spend in order to deliver on each task and output?’ The team leader is usually expected to take responsibility for compiling the work plan and subsequently for ensuring that it is followed in an effective and timely manner. Detailed stakeholder consultation is not usually necessary in work plan development, but it may be useful to cross-check certain aspects with key partners and contacts on the ground – e.g. the timing of fieldwork, the format and location of community consultations, and availability of local partners and field teams.

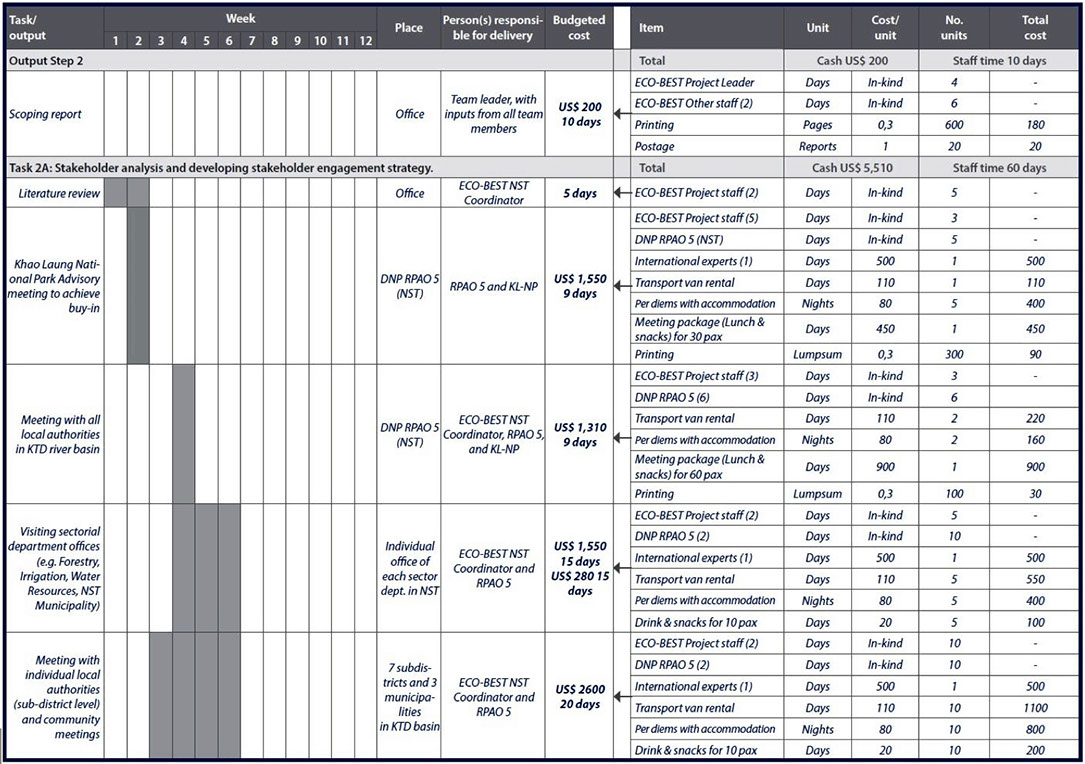

A simple Gantt-type chart is a very clear method of depicting, tracking and communicating work schedules. Template 1C presents a sample work plan. All team members should be aware of their responsibilities and committed to fulfilling them in a timely and cooperative manner (under the guidance and oversight of the Team Leader). A simple budget should be put together which clearly shows what inputs the assessment requires and how much it will cost to provide them.

![]() Template 1C: Example of work plan format (one task from Klong-Thadee river basin, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click

Template 1C: Example of work plan format (one task from Klong-Thadee river basin, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click

Selected references and further guidance for Step 1

The FAO handbook on Participatory Rural Communication Appraisal (PRCA) (Anyaegbunam et al. 2004) describes the procedures and tools for preparing cost-effective and appropriate communication programmes, strategies and materials for development projects. This could be helpful for Task 1 A.

Imprint

Introduction

Step 1:

Getting

organized

Step 3:

Identifying

ecosystem service opportunities

Step 2:

Scoping the

context &

stakeholders

Step 4:

Selecting

policy

instruments

Step 6:

Designing

and agreeing

on the instrument

Step 5:

Sketching

out the

instrument

Step 7:

Planning

for

implementation

Datenschutz

Resources

EN

ES