Once the opportunities to enhance conservation and development goals from an ecosystem services perspective have been characterized, this step aims to select suitable policy and financing instruments to seize the opportunities and help achieve the desired changes. The expected outputs are:

- A list of relevant existing policy and financing instruments with a description how they work.

- A set of proposals for applying existing instruments or creating new ones to seize the ES opportunities that were identified in Step 3.

- A selection of opportunities and suitable instruments to pursue further.

In Step 3, the economic principles were used to identify how gaps could be filled, how imbalances could be addressed or how to make use of new potentials. In sum, the economic principles help identify and structure the opportunities to achieve a behaviour change related to conservation or enhancement of ecosystem services.

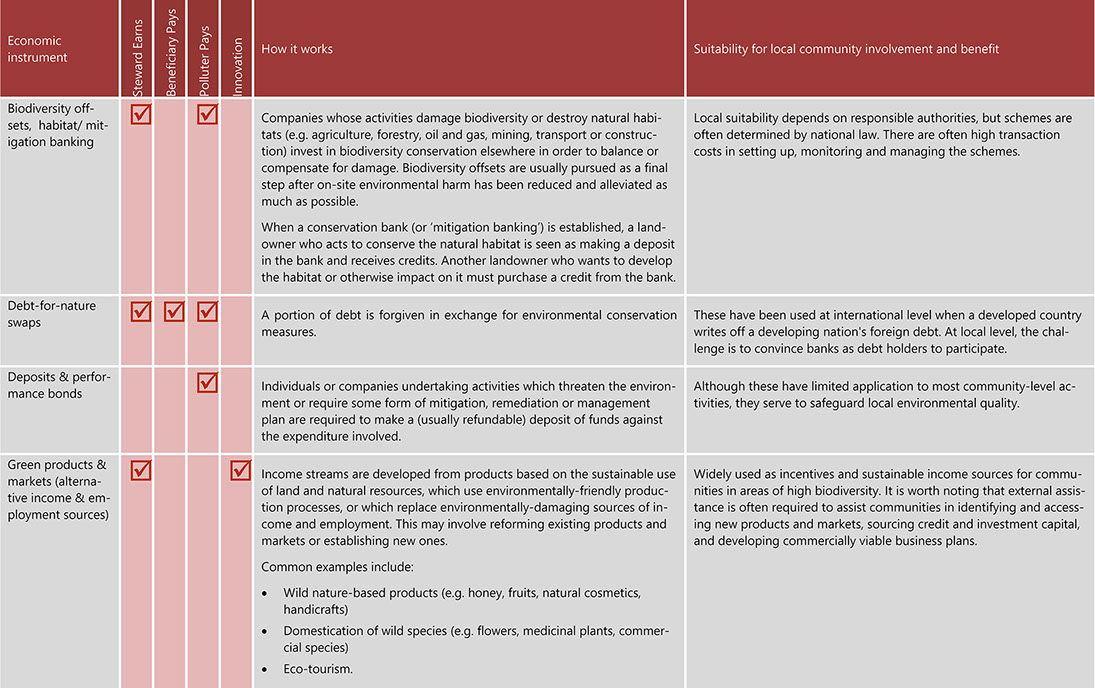

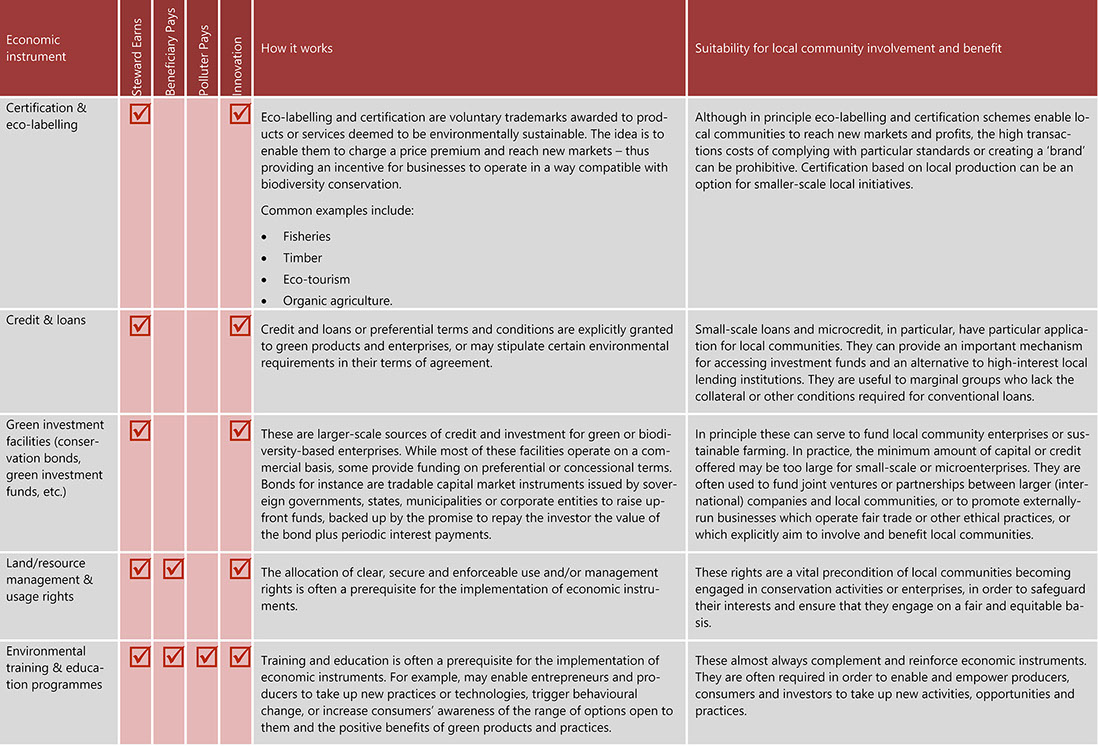

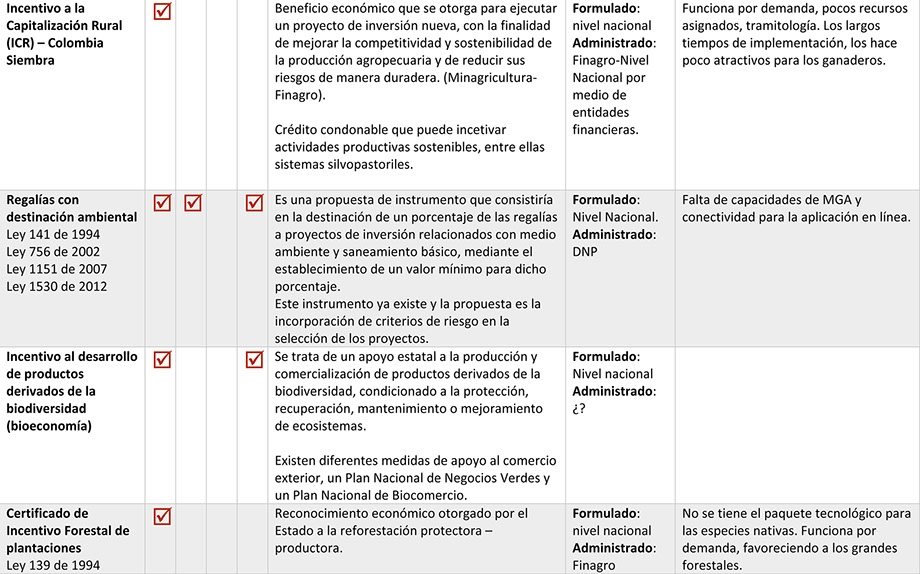

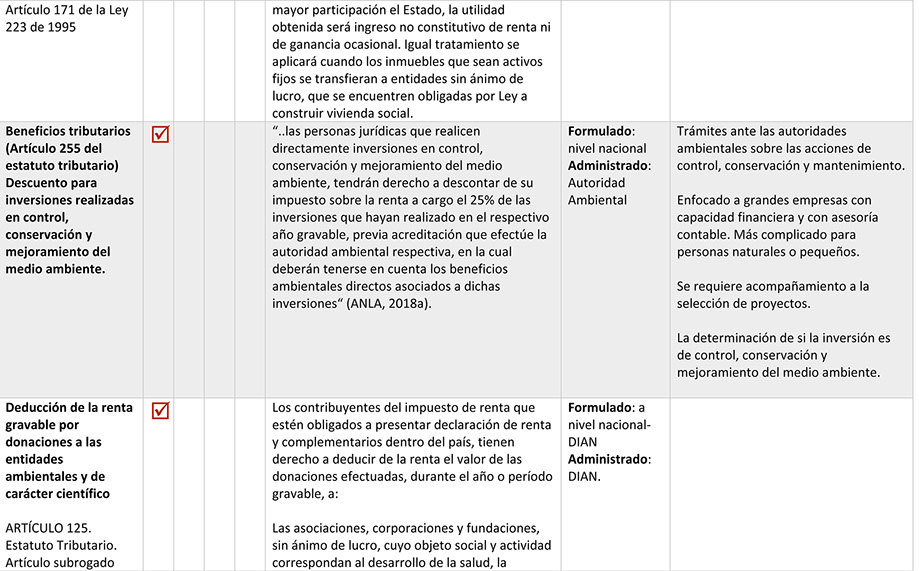

Step 4 consists in identifying how to achieve the desired behaviour change based on the ES opportunities, through policy and financing instruments. These instruments can be seen as concrete tools which motivate (or demotivate) stakeholders to undertake certain actions. Table 3 presents a large list of instruments such as subsidies, compensation, user fees, payment for ecosystem services, green credits, or certification. In summary, whereas the ecosystem services opportunities highlight the possibilities of desirable behaviour change, the policy and finance instruments are the tools that help achieve the behaviour change.

![]() It is important to find a good balance between expert-based analysis and stakeholder engagement!Please click to learn moreAn expert consultation prior to a stakeholder workshop can be very helpful in advancing Task 4A in Step 4. Since knowledge about policy and financing instruments may require a certain degree of expertise and knowledge in the area, expert can help to get an overview of the existing instruments. As alternatives, a literature review can be conducted by the project team or a consultant can be hired.After this consultation, as part of Task 4B, a stakeholder workshop is helpful to match the opportunities identified with the existent instruments, to examine their feasibility and acceptance or to identify the need of new instruments. For this workshop, the information compiled in the experts consultation can be presented in an initial session (here is important to consider short presentations, in a language that participants will understand) and can be complemented by the workshop participants.This information is the base for the following group session. Groups can be built, for instance, according to the project working topics, or specifically to the ecosystem services opportunities which the project wants to further develop.

It is important to find a good balance between expert-based analysis and stakeholder engagement!Please click to learn moreAn expert consultation prior to a stakeholder workshop can be very helpful in advancing Task 4A in Step 4. Since knowledge about policy and financing instruments may require a certain degree of expertise and knowledge in the area, expert can help to get an overview of the existing instruments. As alternatives, a literature review can be conducted by the project team or a consultant can be hired.After this consultation, as part of Task 4B, a stakeholder workshop is helpful to match the opportunities identified with the existent instruments, to examine their feasibility and acceptance or to identify the need of new instruments. For this workshop, the information compiled in the experts consultation can be presented in an initial session (here is important to consider short presentations, in a language that participants will understand) and can be complemented by the workshop participants.This information is the base for the following group session. Groups can be built, for instance, according to the project working topics, or specifically to the ecosystem services opportunities which the project wants to further develop.

Task 4 A: Understanding the policy-scape related to the ecosystem service opportunities

What this task is about

This task serves to understand what is there in terms of policies and financing instruments that influence the protection of biodiversity and ecosystem services and how they work in practice.

Table 3 gives an overview and explanations of policy and financing instruments that are being applied in biodiversity conservation and which stimulate local community involvement and benefit. The second column indicates how the respective policy and financing instruments build on the four principles along which you have identified the opportunities in Step 3: steward earns, beneficiary pays, polluter pays, and innovation. Some instruments are based on one of the instruments, but many combine several of the principles. For instance, PES schemes combine contributions from beneficiaries (or in some cases from degraders) with an incentive mechanism for stewards of ecosystem services, and there is usually a fund to channel and redistribute the money. Developing and promoting an ecological product usually has an innovation component, for instance product innovation or innovative financing) and it supports the stewards in developing and benefiting from the ecological product.

Apart from policies and financing instruments that support the conservation of ecosystem services, it is also important to understand which instruments currently have a negative effect. For instance, in many cases agricultural subsidies are given for activities with negative impact on ecosystem service provision. The incentives for adverse effects may be so strong that small positive incentives would have little effect on behaviour (e.g. of farmers). In that case it may be more effective to advocate for changes in these instruments, e.g. building in the maintenance of biodiversity or ecosystem services as conditions for eligibility to receive the funds.

Keep in mind that existing policies and instruments that assist conservation but especially those that undermine conservation incentives do not necessarily originate from environmental policies, but might stem from different sectorial policies, e.g. agriculture and forestry, energy, transport or trade policy.

Finally, in order to assess the feasibility to work with a specific instrument, it is important to understand ‘multi-level governance’, that is, at which political levels the instruments are initiated and administered. This needs to be considered with respect to the level of project activity. For instance, is the adaptation or application of national level policy instruments in the scope of the project?

![]() There are big differences between countries with respect to which types of policy instruments are already used for conservation and sustainable developmentPlease click to learn moreWhen the ECO-BEST project started in Thailand in 2011, policy instruments for biodiversity conservation were almost exclusively legal instruments, in particular assignation of protected areas and the national park law as legal framework. Almost no positive incentives for biodiversity conservation were in place. One task of the project was to introduce new approaches to conservation band help prepare the capacities and enabling conditions for them to be implementable (trust, institutional arrangements, knowledge, national legal basis, etc.).We encountered a completely different situation when applying the ESO framework in Mexico in 2015 and in Colombia in 2019. In these countries (as in many other Latin American countries), already many incentive-based instruments such as PES were in place and had to be understood. In these countries, before coming up with new instruments, it was important to assess how existing instruments could be improved or applied to new context or regions.

There are big differences between countries with respect to which types of policy instruments are already used for conservation and sustainable developmentPlease click to learn moreWhen the ECO-BEST project started in Thailand in 2011, policy instruments for biodiversity conservation were almost exclusively legal instruments, in particular assignation of protected areas and the national park law as legal framework. Almost no positive incentives for biodiversity conservation were in place. One task of the project was to introduce new approaches to conservation band help prepare the capacities and enabling conditions for them to be implementable (trust, institutional arrangements, knowledge, national legal basis, etc.).We encountered a completely different situation when applying the ESO framework in Mexico in 2015 and in Colombia in 2019. In these countries (as in many other Latin American countries), already many incentive-based instruments such as PES were in place and had to be understood. In these countries, before coming up with new instruments, it was important to assess how existing instruments could be improved or applied to new context or regions.

How to go about Task 4 A

We recommend preparing a list of policy and financing instruments along Template 4A. You will see that the guiding questions in the upper part of the template relates to instruments that work in favour of conservation whereas those in the lower part refer to instruments with adverse effects.

If you already know that the topic of your project takes a specific direction (e.g. promotion of trees on farms or fisheries management) then you may already narrow the search to instruments that are related to that topic. Otherwise the opportunities identified in Step 3 may serve to narrow or at least focus your search.

Taking stock of existing policies was one aspect of the context analysis in Step 2. It is useful to reconsider the context document in Step 2 and specify precisely how they work, including how they build on the different principles to regulate conservation of natural resources and ecosystem service provision. You can also review policy documents. In addition, discussion with political partners and local stakeholders can help ensure that you have not forgotten anything relevant.

![]() Understanding multi-level governance with experts and local actorsPlease click to learn moreIn the Biodiver_CITY project in Costa Rica, ecosystem services opportunities for interurban bio-corridors were identified in a first workshop following Step 3. A second workshop included tasks from Steps 4 and 5. Prior to the second workshop, an expert consultation was conducted regarding the exiting instruments for three main topics identified in the first workshop. The information was classified in the following diagram:

Understanding multi-level governance with experts and local actorsPlease click to learn moreIn the Biodiver_CITY project in Costa Rica, ecosystem services opportunities for interurban bio-corridors were identified in a first workshop following Step 3. A second workshop included tasks from Steps 4 and 5. Prior to the second workshop, an expert consultation was conducted regarding the exiting instruments for three main topics identified in the first workshop. The information was classified in the following diagram: This information was presented during the second workshop with experts and local actors, who were asked to complement and validate the information. This diagram can be helpful in understanding the level of application and estimating the time required for the implementation of instruments. The levels of implementation can be adapted according to the relevant action level for the project. For the Bio-diver_CITY project the levels Gran Área Metropolitana (GAM), Cantón (municipio) and Distrito were included.

This information was presented during the second workshop with experts and local actors, who were asked to complement and validate the information. This diagram can be helpful in understanding the level of application and estimating the time required for the implementation of instruments. The levels of implementation can be adapted according to the relevant action level for the project. For the Bio-diver_CITY project the levels Gran Área Metropolitana (GAM), Cantón (municipio) and Distrito were included.

An expert consultation prior to a stakeholder workshop can be very helpful in advancing Task 4A. Since knowledge about policy and financing instruments may require a certain degree of expertise and knowledge in the area, expert can help to get an overview of the existing instruments. As alternatives, a literature review can be conducted by the project team or a consultant can be hired.

You can also include a discussion on existing instruments in a stakeholder workshop. In this way you may be able to combine a ‘bottom-up’ search with stakeholders and an expert-based ‘top-down’ search. Be aware, however, that depending on their background, local actors may not know all the instruments and an overly technical discussion on their functioning may even lead to frustration.

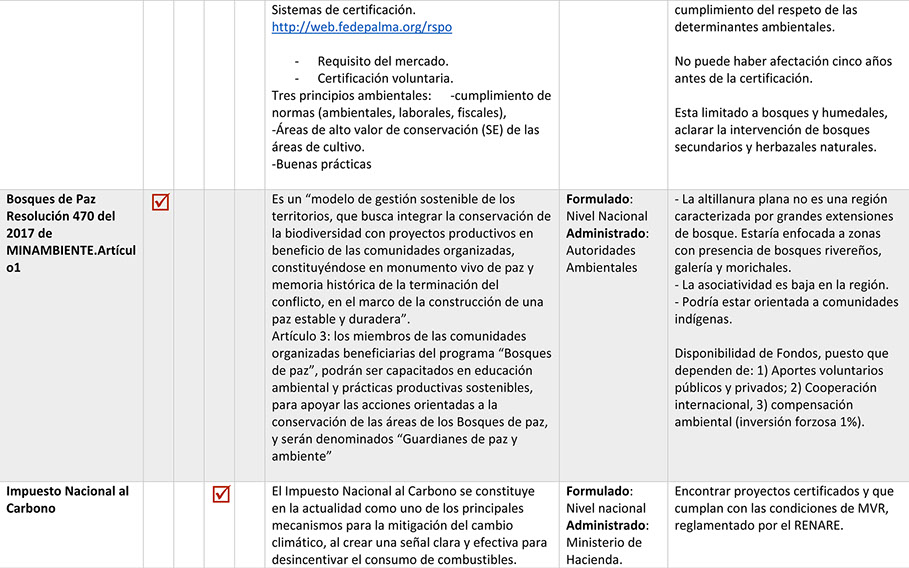

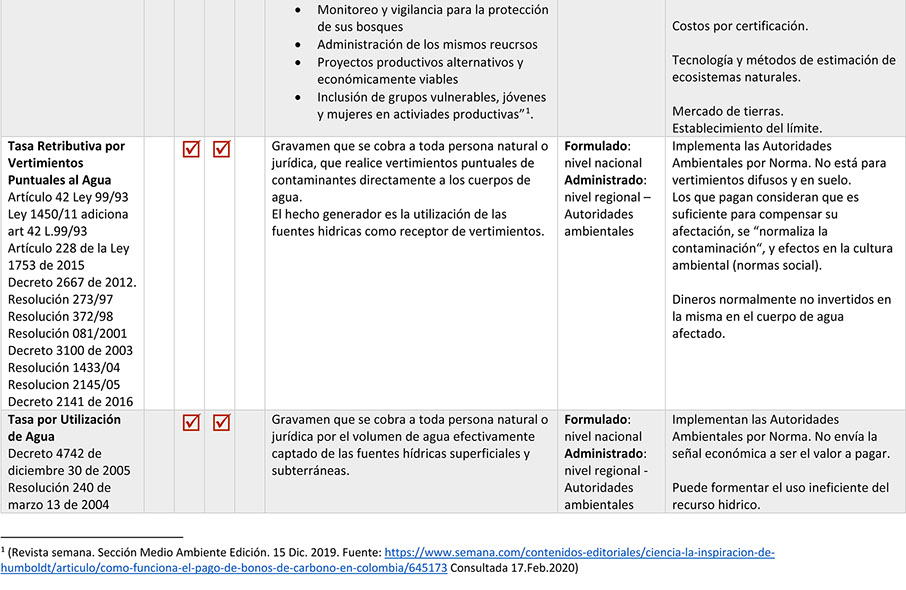

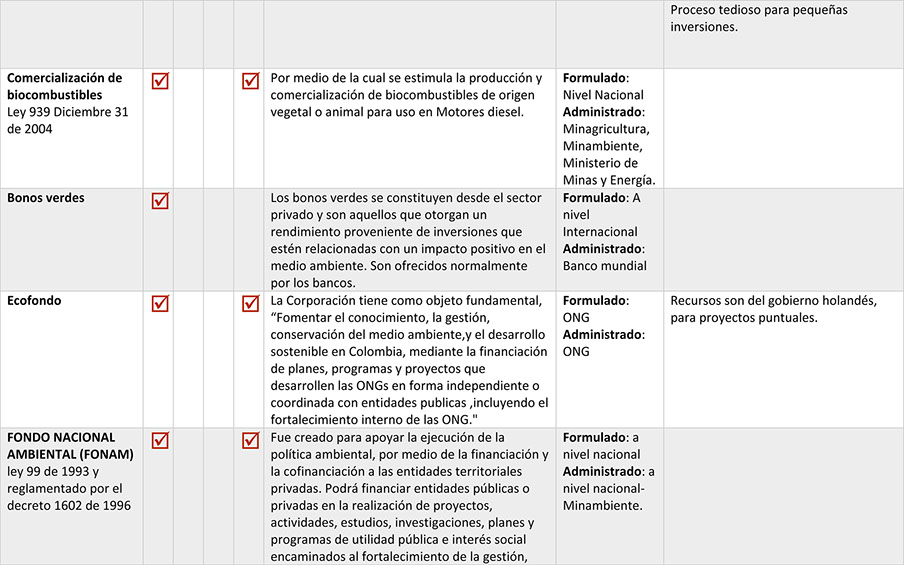

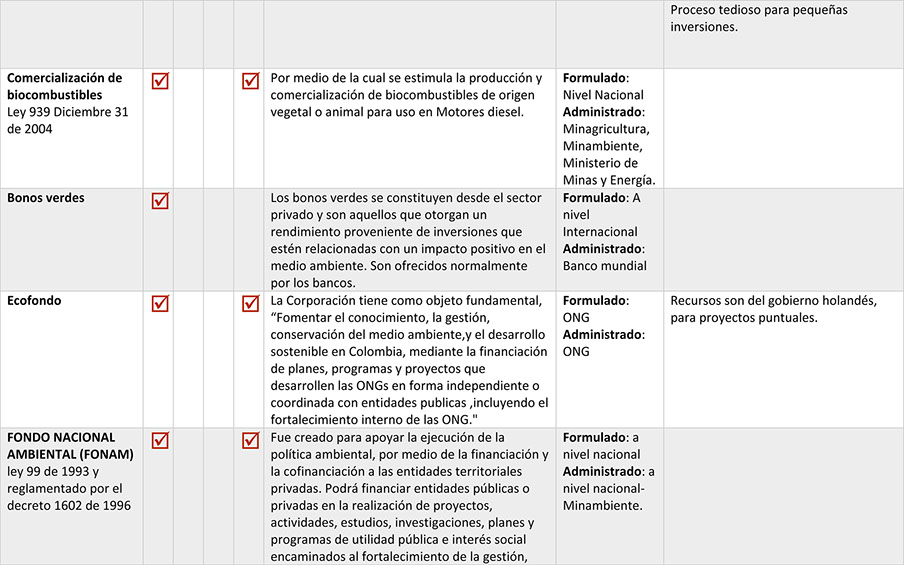

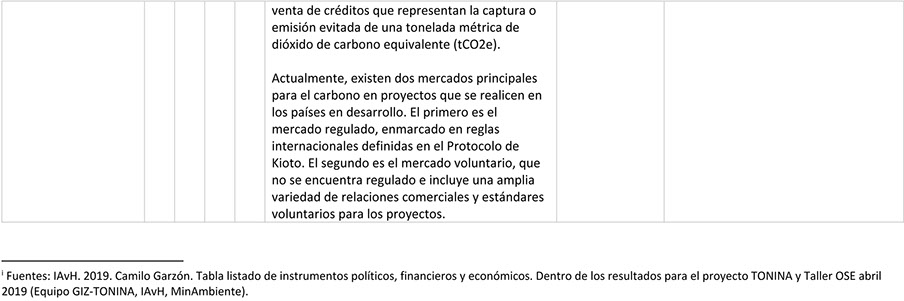

Table 3: Overview of selected policy and financing instruments and how they work according to the four principlesPlease click to learn more

![]()

![]() Template 4A. Understanding the policy context (Example from project TONINA, Colombia) Download filled Download empty

Template 4A. Understanding the policy context (Example from project TONINA, Colombia) Download filled Download empty

Task 4B: Identifying instruments that fit the opportunities

What this task is about

In this task you match the instruments with the opportunities identified in Task 3C. For some opportunities, several instruments will be potentially applicable, for others only one may emerge. As highlighted in Task 4A, it is important to also look at instruments that currently promote behaviour with adverse effects on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Suitability of instruments depends on many factors. Task 4C will go into more detail for selecting promising instruments. At this stage, we recommend asking the following questions:

- Is the core logic of this instrument works in line with the opportunity (in particular according to the four principles)?

- Is the instrument in principle accessible for local application or adaptation?

- Are there no fundamental constraints that would render the instrument infeasible?

It may also occur that for an opportunity there are not yet any existing instruments. In that case, good practice cases from other sectors or from other countries may serve to generate ideas of new instruments.

![]() Building on existing schemes can be effective, but does not always work!Please click to learn moreIn Thadee (Thailand), there seemed to be an opportunity to connect the scheme to an existing agreement between NST municipal authority and Thadee sub-district (the upper watershed), by which the municipality granted free waste disposal (worth 200.000 Baht annually) in return for restoration measures. This was abandoned, however, since this scheme did not work effectively: the right to free waste disposal had become taken for granted while the restoration measures remained unclear and unmonitored. Moreover, local authorities did not respond well to the idea of improving the situation by defining clear actions, time lines, etc.

Building on existing schemes can be effective, but does not always work!Please click to learn moreIn Thadee (Thailand), there seemed to be an opportunity to connect the scheme to an existing agreement between NST municipal authority and Thadee sub-district (the upper watershed), by which the municipality granted free waste disposal (worth 200.000 Baht annually) in return for restoration measures. This was abandoned, however, since this scheme did not work effectively: the right to free waste disposal had become taken for granted while the restoration measures remained unclear and unmonitored. Moreover, local authorities did not respond well to the idea of improving the situation by defining clear actions, time lines, etc.

![]() Education and informationPlease click to learn moreEducation and information: Learning about and connecting with nature, or raising awareness about biodiversity and ecosystem service degradation, often encourage the acceptance of new policies, or increase participation in voluntary conservation and management measures. In the long run, true intrinsic appreciation of and connection with nature may be even more important to the success of conservation measures than economic incentives.

Education and informationPlease click to learn moreEducation and information: Learning about and connecting with nature, or raising awareness about biodiversity and ecosystem service degradation, often encourage the acceptance of new policies, or increase participation in voluntary conservation and management measures. In the long run, true intrinsic appreciation of and connection with nature may be even more important to the success of conservation measures than economic incentives.

How to go about Task 4 B

Template 4B serves to look systematically at each of the opportunities that you identified in Task 3C link. For a first broad matching it should help to look at the four principles. The opportunities in Step 3 were derived and ordered along these principles, and Template 4A asked you to clarify for each instrument which principles they are based on. Hence, looking at the principles can help you identify potential matches.

Then, check whether those potential matches seem in principle suitable for your (local) context. The overview table of instruments on the ‘resources’ page as well as Table 3 above include information on the suitability of different instruments for local management and policy. In Task 4A you were asked to include this information for your specific context. Of course you can leave out instruments for which you have fundamental concerns.

To get inspiration or concrete ideas about potential new instruments to consider, we recommend a benchmarking exercise that looks at instruments that have been applied in other countries. Again, you can look at the overview table on the ‘resources page’, which provides examples from case studies where each of the instruments have been applied. You can also look at the references and links below. In addition, you can also discuss with national or international experts. The international case studies should inspire and help your team to derive concrete ideas about what could work for you. Bear in mind, however, that devising appropriate instruments often requires considerable innovation, because of the unique features of each setting and case. Experiences in other areas are useful to know about but not often directly transferable.

Template 4B also asks you to give reasons why you think an instrument may be a good match, and to think about possible risks and challenges. It can be very helpful to discuss these points with someone experienced in implementing policy and financing instruments for conservation.

The matches of opportunities and instruments can be co-developed and ground-proved with local stakeholders, for instance in a workshop setting. Ideas and reactions from local actors may provide valuable information with respect to feasibility and desirability of opportunities and instruments. As noted already in Task 4A, however, you need to take care not to expect too much technical expertise from local actors and not to frustrate them with an overly technical discussion.

![]() Workshops on ecosystem service opportunities or policy instruments can become spaces for communication within local actors that would not take place otherwisePlease click to learn moreIn the Biodiver_CITY project in Costa Rica, experts on different topics (urban planning, water resources management, urban restoration) were invited to the workshop for Step 4 and 5. This workshop served as a communication space among representatives from the Ministry of the Environment and Energy, the National System of Conservation Areas, the Urban and Housing National Institute and representatives from the public administration of the national, regional and local levels. In the group session on instruments for urban restoration, the overlapping of functions in existent regulations from different public entities was identified.Given the extensive legislation on the subject and its different levels of implementation, these actors have related functions, but there are typically few spaces for information and exchange of experiences. The group sessions served to elaborate a protocol that integrates the different regulations and allows a clearer path of action for the actors involved in their implementation.While it was not yet clear which instrument the project would pursue for implementation, there were clear commitments at the end of the workshop among the participants to follow up on the proposed activities.

Workshops on ecosystem service opportunities or policy instruments can become spaces for communication within local actors that would not take place otherwisePlease click to learn moreIn the Biodiver_CITY project in Costa Rica, experts on different topics (urban planning, water resources management, urban restoration) were invited to the workshop for Step 4 and 5. This workshop served as a communication space among representatives from the Ministry of the Environment and Energy, the National System of Conservation Areas, the Urban and Housing National Institute and representatives from the public administration of the national, regional and local levels. In the group session on instruments for urban restoration, the overlapping of functions in existent regulations from different public entities was identified.Given the extensive legislation on the subject and its different levels of implementation, these actors have related functions, but there are typically few spaces for information and exchange of experiences. The group sessions served to elaborate a protocol that integrates the different regulations and allows a clearer path of action for the actors involved in their implementation.While it was not yet clear which instrument the project would pursue for implementation, there were clear commitments at the end of the workshop among the participants to follow up on the proposed activities.

![]() Template 4B. Associate the instruments (existing or new) with the opportunities identified in task 3C (Example Puerto Carreño, Colombia) Download filled Download empty

Template 4B. Associate the instruments (existing or new) with the opportunities identified in task 3C (Example Puerto Carreño, Colombia) Download filled Download empty

Task 4 C. Selecting opportunities and appropriate instruments

What this task is about

In most cases, your project will not be able to further pursue all the opportunities and instruments that have been identified up to here. There will usually be a need to prioritize and make a selection. However, the information gathered and its analysis and validation with local actors represent in any case a valuable working input that other projects, public or private stakeholders may pick it up later.

![]() A document with a catalogue of the identified opportunities and policy instruments can help other projects or local actors to access the information Please click to learn moreIn the TONINA project in Colombia, as a result of Step 3 workshops in four municipalities, 7-12 opportunities were identified for each municipality. As part of the project's capacity development and communication strategy, a booklet was designed to accompany the process of joining and taking over the new administrations after the elections (regional and local). The booklet includes a chapter on the opportunities for action, which describes how the identification process was carried out and the opportunities that the project can develop according to the stipulated resources and time. The booklet also presents the remaining opportunities, which can serve as information for other projects.

A document with a catalogue of the identified opportunities and policy instruments can help other projects or local actors to access the information Please click to learn moreIn the TONINA project in Colombia, as a result of Step 3 workshops in four municipalities, 7-12 opportunities were identified for each municipality. As part of the project's capacity development and communication strategy, a booklet was designed to accompany the process of joining and taking over the new administrations after the elections (regional and local). The booklet includes a chapter on the opportunities for action, which describes how the identification process was carried out and the opportunities that the project can develop according to the stipulated resources and time. The booklet also presents the remaining opportunities, which can serve as information for other projects.

The selection can depend on many different aspects. Checklist 4C provides an overview of typical criteria and specific guiding questions to consider in the selection process.

![]() Check list 4C. Possible criteria for selecting opportunities and instruments [Download]Please click to learn more

Check list 4C. Possible criteria for selecting opportunities and instruments [Download]Please click to learn more

It is important to keep in mind that new instruments are typically most effective in combination with existing ones and also with a combination of measures. Most of the time, there are also several sustainability challenges within the same area, and a mix of several instruments is more likely to address them successfully than a single one. For instance, a voluntary scheme by which the beneficiaries of ecosystem services support ecological land management or conservation actions can improve on the minimum requirements already established by direct regulation (such as rules for land use within protected areas, limits to fertiliser use, legal restrictions on hunting or logging, etc.).

How to go about Task 4 C

Checklist 4C offers an overview of criteria that you could take into account for selecting the opportunities and instruments that you actually want to advance and help develop. We recommend that, based on the checklist, you first define the selection criteria that you want to take into account. For the actual selection, different procedures are possible. You could, for instance, simply have an open discussion within your project team and agree on which opportunities and instruments to pursue. In some cases this may be rather obvious and the discussion will mainly serve to ensure that you have not missed out on any relevant aspect and to confirm your choice.

When there are many options and the selection is not so obvious, a simple version of a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) can support your selection process (see Example from TONINA, Colombia in the box). For that, you have to a) define the set of criteria you want to consider, b) assign weightings to each of the criteria according to their importance, and c) assign for each of the options comparable values that represent how well they fare for each of the criteria (e.g. in a voting procedure with your team or experts consultation). If you then multiply for each option the weights with the value and add them up, you receive a final score for each option. Be aware that MCDA results offer guidance, but may not always be the decisive factor for the selection decision. It may not be adequate especially if some criteria are not “substitutable”. For instance, if there is a strong moral concern or high risk of negative side-effects or failure, this may be a reason to categorically refrain from selecting this option, even if it scores high on other dimensions. The same may be the case if you simply do not have the resource capacity or the required political support to advance a particular option. You could also define “no-go” criteria according to which you exclude options from further considerations (e.g., insufficient institutional capacity, no access to intervention zone, high conflict potential), and conduct an MCDA only for a smaller set of remaining options.

![]() Example: Selection process in the TONINA project, Colombia Please click to learn moreWith the information from information collection in Steps 2-4 as well as the workshops in the four intervention sites of the TONINA Project, between 7 - 12 opportunities were identified for each site. For the selection of opportunities, the GIZ team formulated 6 selection criteria and conducted a simple multi-criteria decision analysis exercise.

Example: Selection process in the TONINA project, Colombia Please click to learn moreWith the information from information collection in Steps 2-4 as well as the workshops in the four intervention sites of the TONINA Project, between 7 - 12 opportunities were identified for each site. For the selection of opportunities, the GIZ team formulated 6 selection criteria and conducted a simple multi-criteria decision analysis exercise. Each selection criterion (see table) was evaluated for each opportunity with values from 1 to 3, with 3 being the highest value. The opportunities with the highest scores were the basis for a first selection. 2 - 6 opportunities were pre-selected for each site.A meeting was then held between the GIZ and UFZ teams (8 people) to make a selection of opportunities. For this exercise, the 4B template was prepared for the intervention sites, with instruments associated with the opportunities initially prioritized by GIZ, describing the reasons in favor and the risks for each one. This information was presented and discussed, being complemented especially by the team working in the region (with local information on feasibility) and then a vote was taken considering the following criteria: 1) Project resources (a maximum of 2 opportunities could be selected per intervention site) and 2) Accessibility of the intervention site. Each participant voted for two opportunities for each intervention site, justifying their decision. Through a guided discussion, the team agreed to select those two opportunities for each intervention site that received the most votes.

Each selection criterion (see table) was evaluated for each opportunity with values from 1 to 3, with 3 being the highest value. The opportunities with the highest scores were the basis for a first selection. 2 - 6 opportunities were pre-selected for each site.A meeting was then held between the GIZ and UFZ teams (8 people) to make a selection of opportunities. For this exercise, the 4B template was prepared for the intervention sites, with instruments associated with the opportunities initially prioritized by GIZ, describing the reasons in favor and the risks for each one. This information was presented and discussed, being complemented especially by the team working in the region (with local information on feasibility) and then a vote was taken considering the following criteria: 1) Project resources (a maximum of 2 opportunities could be selected per intervention site) and 2) Accessibility of the intervention site. Each participant voted for two opportunities for each intervention site, justifying their decision. Through a guided discussion, the team agreed to select those two opportunities for each intervention site that received the most votes.

Selected references and further guidance for Step 4

Guidance on the selection of economic instruments:

The Guide on ‘The Polluter Pays Principle’ (Cordato 2010) provides an overview on how to use the principle in environmental policies (Task 4A).

The publication ‘Incentive and Market-Based Mechanisms to Promote Sustainable Land Management’ (CATIE 2012) presents an analytical framework and tool for how to use incentive and market-based mechanisms (IMBMs) to promote investments in sustainable land management practices (SLMPs) (Task 4C).

The report on ‘Economic Instruments in Biodiversity-Related Multilateral Environmental Agreements’ (UNEP 2004) provides an overview of economic instruments and explains their potential role for meeting policy goals in the context of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, and the Ramsar Convention (Task 4C).

Chapter 2 of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment report ‘Ecosystems and human well-being, Policy Responses, Findings of the Response’ (Chambers, W. B.; Toth, F. L. 2005) presents a basic overview of the wide range of policy instruments and measures (including economic ones) to regulate human interaction with ecosystems (Task 4C).

UNEP (2009) has developed a Training Resource Manual on ‘The Use of Economic Instruments for Environmental and Natural Resource Management’ that provides detailed descriptions for understanding and selecting economic instruments, and can be used for training purposes (Task 4C).

Chapter 4 of the Conservation Finance Guide (CFA 2008) presents a description of various conservation finance mechanisms (Task 4C).

Chapter 5 of the Ecosystem Services: A Guide for Decision Makers (WRI 2008a) provides an extensive overview of policy instruments (Task 4A).

Full References:

Cordato, R.E. (2010): The Polluter Pays Principle: A Proper Guide for Environmental Policy, Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation Studies in Social Cost, Regulation, and the Environment: No. 6, Washington. URL: http://iret.org/pub/SCRE-6.PDF (accessed December 2017)

UNEP (2004): Economic Instruments in Biodiversity-Related Multilateral Environmental Agreements, Nairobi. URL: http://www.unep.ch/etb/publication/EconInst/ecoInstBioMea.pdf (accessed December 2017)

Chambers, W. B. & Toth, F. L. (2005): Typology of Responses (Chapter 2). In: Chopra, K. et al. (Ed.): Ecosystems and human well-being, Vol. 3: Policy Responses, Findings of the Responses Working Group (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Series), Chicago.

UNEP (2009): Training Resource Manual: The Use of Economic Instruments for Environmental and Natural Resource Management (First Edition). United Nations Environment Programme, Geneva. URL: http://www.unep.ch/etb/publications/EI%20manual%202009/Training%20Resource%20Manual.pdf (accessed December 2017).

Imprint

Introduction

Step 1:

Getting

organized

Step 3:

Identifying

ecosystem service opportunities

Step 2:

Scoping the

context &

stakeholders

Step 4:

Selecting

policy

instruments

Step 6:

Designing

and agreeing

on the instrument

Step 5:

Sketching

out the

instrument

Step 7:

Planning

for

implementation

Datenschutz

Resources

EN

ES